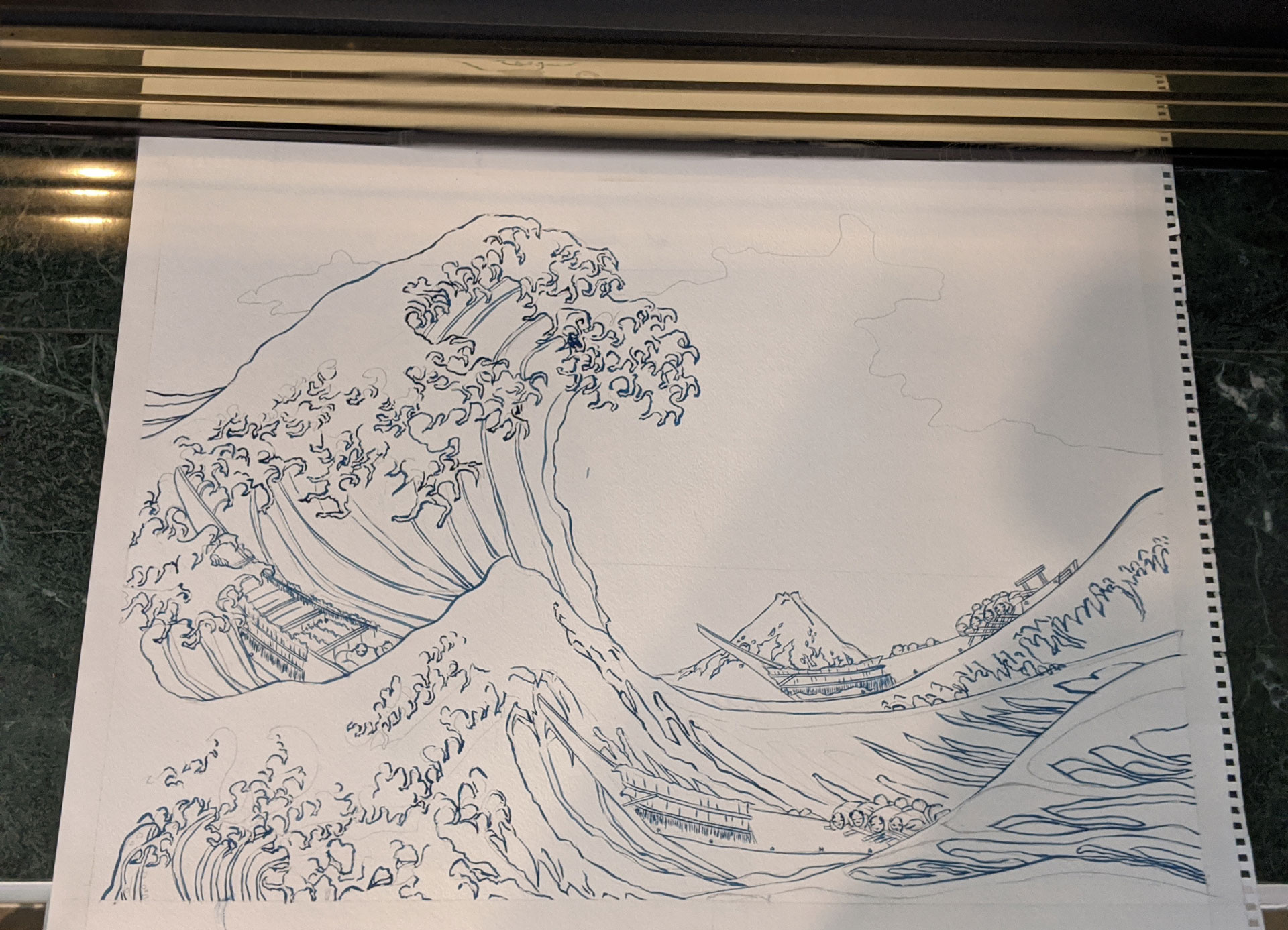

There are images that don’t just represent nature; they behave like nature. Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa (often called The Great Wave) is one of them: it surges, curls, threatens, and then—if you keep looking—turns into a kind of joke about scale. Mount Fuji, the sacred anchor, becomes a small triangle tucked inside the wave’s hollow.

I return to this wave the way you return to a familiar path: not to arrive anywhere, but to notice what’s different in you each time.

Why this wave keeps moving

Hokusai made The Great Wave as part of Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, around ca. 1830–32. The scene is simple: three boats, an enormous curling wave, and Fuji in the background. Yet the composition is strange in a way that feels alive—almost physiological. The wave is both water and claw, both danger and a kind of theatrical gesture. Museums describe the print as “Under the Wave off Kanagawa,” emphasizing that we are not admiring the wave from a safe distance—we are under it.

What fascinates me is that the image is not only about survival; it’s also about perception. Hokusai’s perspective tricks the eye into accepting that Fuji—Japan’s grand mountain—can be made small without being made unimportant. That’s already a philosophical statement, whether he meant it or not.

The “useful useless” of a wave

Zhuangzi has that famous theme: 无用之用—the usefulness of what looks useless. A tree spared the axe because its wood is “good for nothing,” and thus it lives long enough to shade travelers.

Art works like that. A painting doesn’t fix your roof or pay your taxes. It’s “useless.” And yet, in the best cases, it quietly re-tunes how you inhabit the day—how you look at weather, risk, effort, and the comedy of taking yourself too seriously.

This is why I love practicing with the Great Wave: it’s not a “productivity image.” It doesn’t reassure. It says: the world is large; your plans are small; keep rowing anyway. And then it adds a second, gentler line: also, look—Fuji is still there.

Making my own wave (watercolor as non-forcing)

My version—The Great Wave off Kanagawa Watercolor—is a hand-painted original watercolor, 18” × 24”, unframed. Watercolor is the perfect medium for this subject because it refuses to be completely controlled. Pigment blooms where it wants; edges soften; mistakes become weather. If you fight it, it looks stiff. If you cooperate, it looks like water.

That’s the part that feels closest to Dao practice: not “doing nothing,” but not forcing—letting the material show you what it can do, then meeting it halfway.

On the product page I’ve included both the finished painting and a draft study, because I want the process to stay visible. The wandering matters as much as the arrival.

A small Buddhist note: waves are honest

In Buddhism, the mind is often compared to a restless surface—thought, feeling, reaction, story. A wave rises, crests, collapses. The point is not to win against waves. The point is to see them clearly, and to stop mistaking every crest for a final verdict.

This image is a reminder that impermanence isn’t a slogan; it’s a texture. In watercolor, you can’t freeze the water at the perfect moment—you can only practice being present while it moves.

If you want to live with this wave

I don’t think art needs to be “sold” with pressure. If you’re the kind of person who enjoys wandering, play, and that oddly comforting feeling of being small under a big sky, then this piece may feel like a companion.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa Watercolor is currently available as an original (18” × 24”, unframed).

If you’d like to see it, I’d start there—and if it speaks to you, you’ll know.