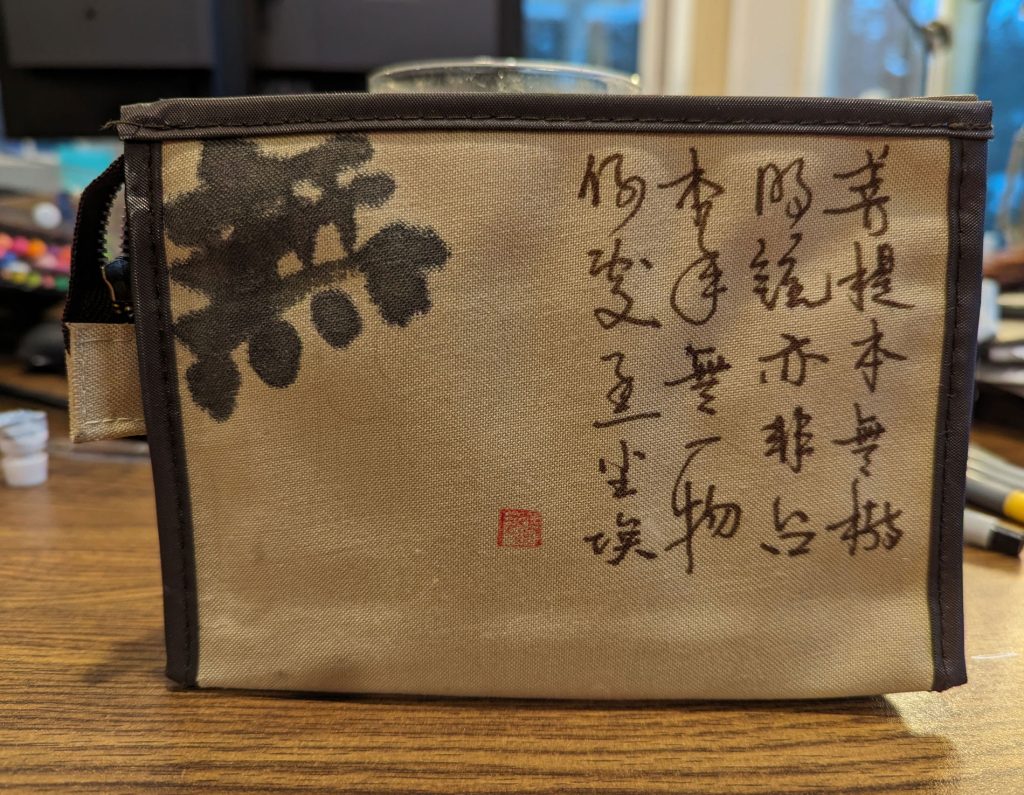

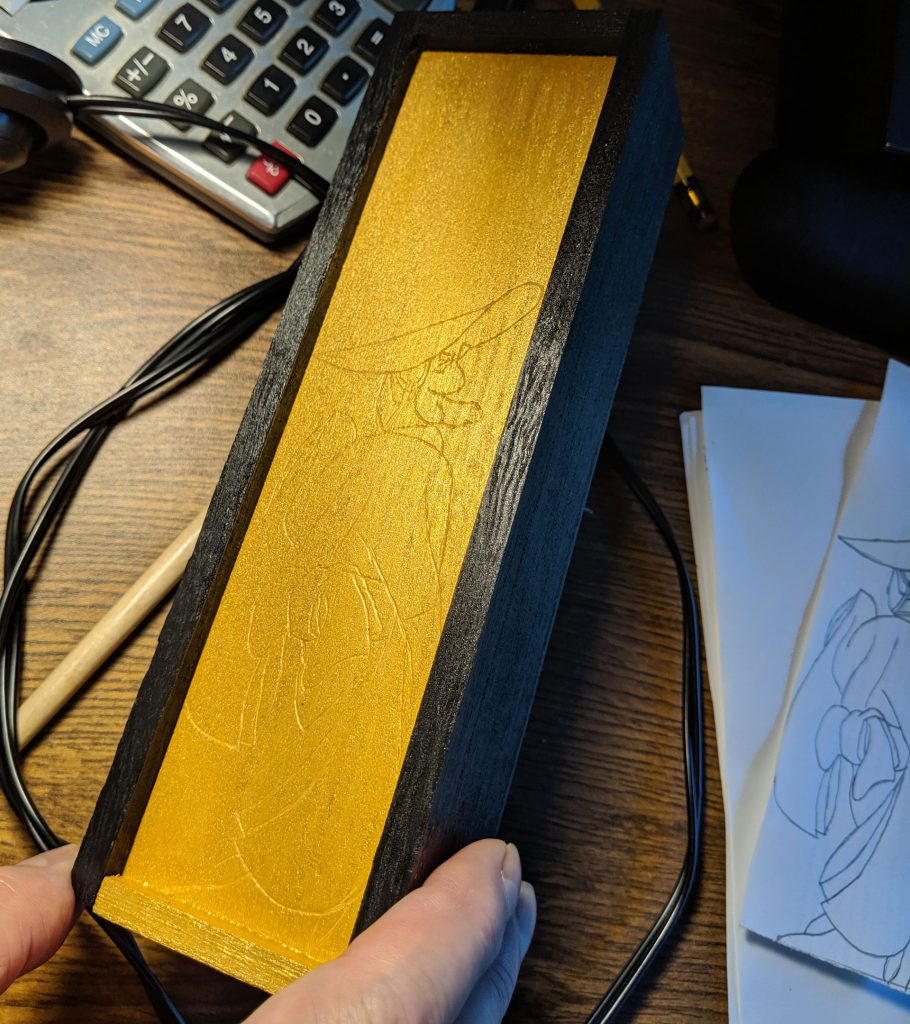

A few years ago, when I visited my dear sister in Japan, she gave me an Omamori. I still own it and I cherish it. The past weekend was the Chinese New Year, and I made some Omamori bags with Japanese vintage silk. As the classic Buddhists say, the wish word inside is “every day is a beautiful day”. A small bottle containing gold leaf, which means that everyone needs good luck and wealth.

Introduction:

Omamori (御守 or お守り) are Japanese amulets commonly sold at Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples, dedicated to particular Shinto kami as well as Buddhist figures, and are said to provide various forms of luck or protection.

Origin and usage

The word mamori (守り) means protection, with omamori being the sonkeigo (honorific) form of the word. Originally made from paper or wood, modern amulets are small items usually kept inside a brocade bag and may contain a prayer, religious inscription of invocation. Omamori are available at both Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples with few exceptions and are available for sale, regardless of one’s religious affiliation.

Omamori are then made sacred through the use of ritual, and are said to contain busshin (spiritual offshoots) in a Shinto context or kesshin (manifestations) in a Buddhist context.

While omamori are intended for temple tourists’ personal use, they are mainly viewed as a donation to the temple or shrine the person is visiting. Visitors often give omamori as a gift to another person as a physical form of well-wishing.

Design and function

An image an Omamori style Gohonzon distributed by Soka Gakkai for members during on travels away from home.

The amulet covering is usually made of brocaded silk and encloses papers or pieces of wood with prayers written on them which are supposed to bring good luck to the bearer on particular occasions, tasks, or ordeals. Omamori are also used to ward off bad luck and are often spotted on bags, hung on cellphone straps, in cars, etc.

Omamori have changed over the years from being made mostly of paper and/or wood to being made out of a wide variety of materials (i.e. bumper decals, bicycle reflectors, credit cards, etc.). Modern commercialism has also taken over a small part of the creations of omamori. Usually this happens when more popular shrines and temples cannot keep up with the high demand for certain charms.

According to Yanagita Kunio (1969):

Japanese have probably always believed in amulets of one kind or another, but the modern printed charms now given out by shrines and temples first became popular in the Tokugawa period or later, and the practice of a person wearing miniature charms is also new. The latter custom is particularly common in cities.

Omamori may provide general blessings and protection.